An orderly unwinding

The government's decision to end the scheme for hiring care workers direct from overseas is reasonable and evidence-based

Yesterday’s attacks on Labour for scrapping care worker visas were over-blown. Yvette Cooper and Wes Streeting have taken an evidence-based decision that is reasonable under the circumstances. It may come with some risks. But it does not create another crisis in social care.

Labour is right to seek to reduce net migration from the absurdly high level reached under the Tories. Action will help see off the threat from Reform and build a well-functioning labour market. But efforts to reduce migration overall should never be at the expense of highly-skilled migrants who will power the government’s plans for growth. The UK needs to attract more of the brightest talent.

Squaring the circle means reining in migration whenever jobs can be filled in other ways. That applies to social care. Critically, the number of people coming from overseas to work in the sector has already plummeted. There are two statistics relevant to social care migration and both are well below their recent peaks.

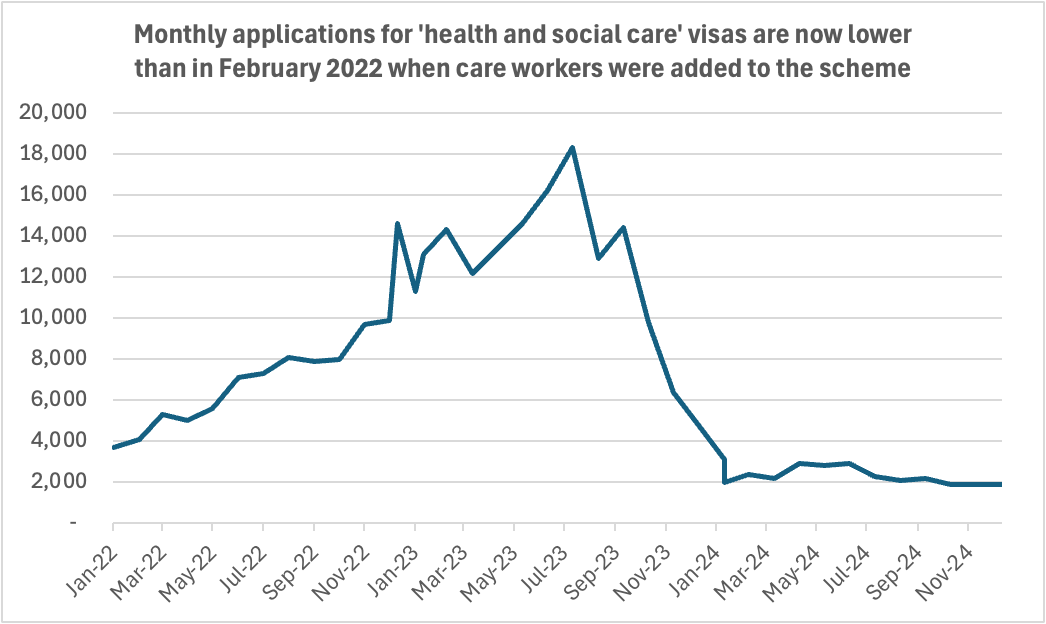

First, monthly health and care visa applications declined by 90 per cent between August 2023 and January 2025. The government does not publish separate numbers for health and care workers using the scheme. But the number of applications is now lower than before this visa route was opened to social care. There are now only 2,000 applications per month across both health and care and the NHS has been far less affected than social care by recent rule changes. It is therefore safe to assume that under 1,000 social care visas applications are being made each month. The number could be much lower.

Source: Home Office

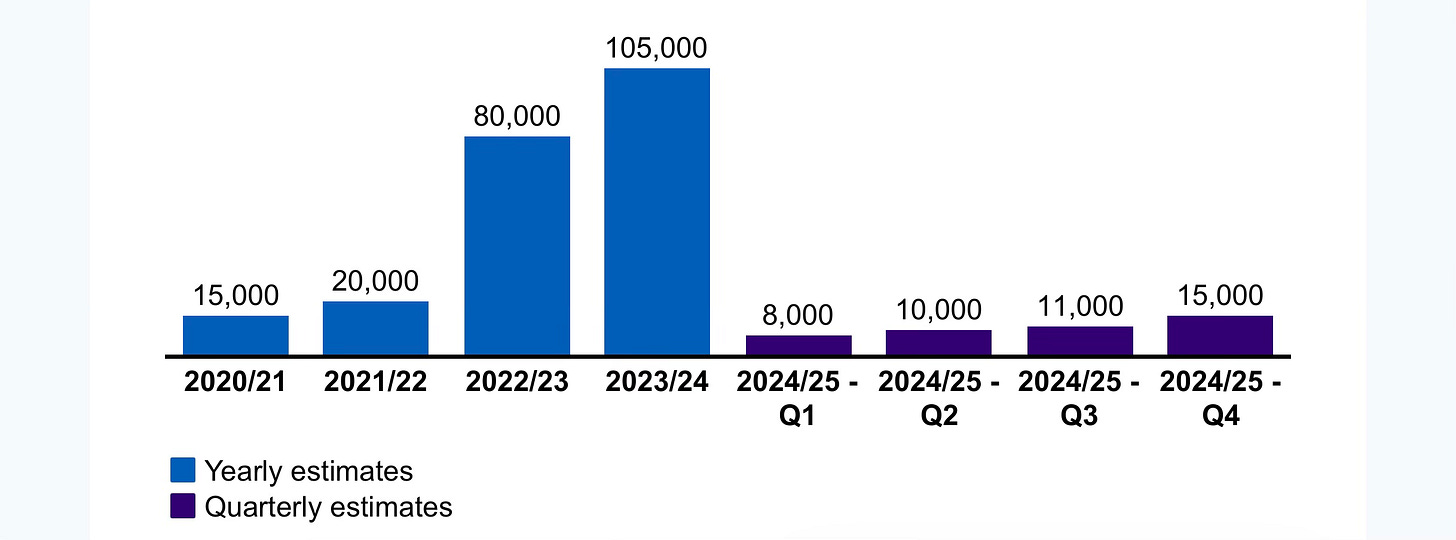

Second, the number of new arrivals being hired by independent care providers fell 41 per cent between 2023/24 and 2024/25. According to Skills for Care’s estimates in the chart there are now roughly 4,000 to 5,000 hires each month by independent care providers from people who recently arrived in the UK. The percentage fall is lower than with the Home Office’s visa statistics because this group does not just comprise workers recruited abroad under the health and social care track. Recent migrants are included irrespective of which route they used to enter the UK. It is therefore a ceiling on the level of care-related migration.

Source: Skills for Care

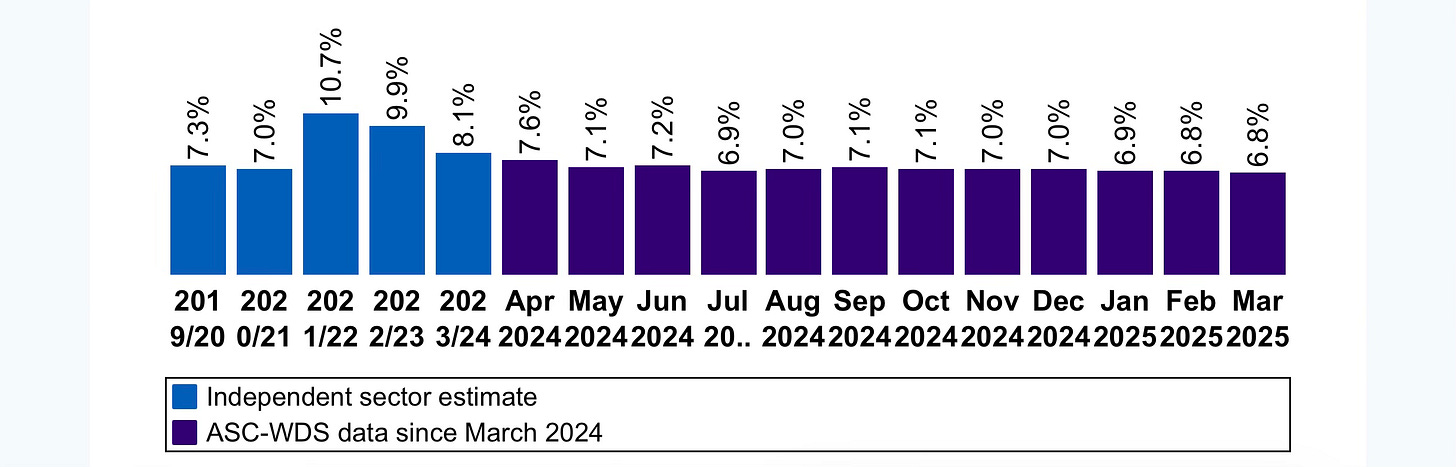

The evidence shows that adult social care providers have been able to respond to the decline in migrant numbers. It is true that the sector still faces recruitment challenges. But over the last year the vacancy rate for independent care providers has decreased from 8.1% to 6.8%, just as the changes to visa rules were kicking-in. The chart from Skills for Care shows how vacancies are now lower than before the pandemic.

Source: Skills for Care

Ministers cannot know for sure that ending care worker visas will not cause care providers pain. But the numbers from the last 18 months should give them some confidence.

Treating care workers as a shortage occupation is a recent innovation. Care worker visas only started in February 2022 at a time when vacancy rates in the sector were surging after the pandemic. As Covid restrictions eased the number of recent migrants joining independent care providers shot up from 20,000 in 2021/22 to 105,000 in 2023/24. Even more telling, the proportion of social care workers filled by UK-born workers fell from 84 per cent to 75 per cent. Care worker visas were an effective and important response to a post-Covid crisis. But an orderly unwinding of the measure is reasonable.

The big fall in care worker visas so far has been associated with better enforcement of the rules, registration requirements for rogue recruitment agencies and a prohibition on care workers bringing dependents. There may have been a fall in employer demand too. After all it is easier to recruit a worker close to home if you can, rather than sponsor one from overseas.

Social care will continue to employ lots of recent migrants. People who have come to the UK for other reasons, mainly as dependents, will be able to apply for jobs in the sector. So will foreign care workers who are already here who want to change employer. And perhaps the mooted EU youth mobility scheme will be another source of new blood. But adult social care can probably get by without recruiting sponsored workers direct from overseas.

The government’s priority should be to increase employment in the sector while pushing up the share of care workers who are UK citizens or long-term residents, at least back up to pre-Covid levels. That will mean making adult social care a sector of choice. Labour already has big plans in this area and it needs to get on with implementing them.

The Employment Rights Bill will create a Fair Pay Agreement for social care negotiated by care providers and unions. This is almost certain to introduce a sector minimum wage set above the National Living Wage, with terms and conditions for care workers that are better than the statutory minimum. Higher standards will attract more workers so for the sake of domestic recruitment ministers need to implement the new arrangement fast. They should also introduce a career and skills framework to both invest in care jobs and improve the quality of care.

Making social care jobs better will cost money of course. Social care employers, unions and consumer champions should not get too distracted by changes to the migration rules, which are achievable and politically necessary. It is the debate about the financing of care that really matters. The next big choice for Labour is how much money to give to social care in the summer spending review.