Why the chancellor is right to reform pension tax relief

Even if it isn't music to the ears of the pensions industry

Yesterday I tried to persuade 500 pensions professionals that their industry should receive a lot less tax relief. I’m not going to pretend I won the room over at the PLSA annual conference. But the debate was more balanced and open-minded than you might expect.

The backdrop is that Rachel Reeves needs to raise tens of billions of pounds in extra revenue. She has said she won’t touch the rates of the big four taxes – income tax, national insurance, VAT and corporation tax. Politically palatable options that target high wealth will only generate small amounts. It means that a tax raid on pensions is the ‘least bad’ option at her disposal.

The chancellor’s options

At the 30 October Budget Reeves is likely to make at least two changes:

First, it looks like she will reform how defined contribution (DC) pensions are taxed when people die. This is to close a tax planning loophole that exempts DC pension pots from inheritance tax, and in some cases income tax for descendants too.

Second, there is speculation she will levy National Insurance Contributions on employer pension contributions. This would deal with an odd quirk of the tax system, which sees employer contributions exempted from NICs despite there being no compensating levy at a later stage.

The chancellor may also reduce the amount that can be taken as a tax-free lump sum. There is a sound case for reform here. The idea behind pension tax relief is that your pension contributions go untaxed because you will eventually pay on your retirement income. But when it comes to the 25% lump-sum, the money is always tax free.

Reducing the limit on the lump-sum from £268,000 to, say, £100,000 would be unpopular – even though a tax-free payment of six figures is still a huge amount for most people. I expect the chancellor to move cautiously. Perhaps she will freeze the allowance in cash terms, or gradually reduce it for successive age cohorts? Those who are at or near the minimum age for drawing a private pension would then not lose a benefit they had reason to expect.

There are two more big changes Reeves could consider later, but they will not feature in this Budget. First is reform of the income tax system to create a single flat-rate of relief, instead of using people’s marginal tax rate. For now the Treasury has ruled this out for fear it will hit public sector pensions. This makes sense because a rushed reform could have unintended consequences. But the chancellor should announce a consultation and request detailed technical work. With careful planning, public sector pension schemes could be compensated for any changes, to avoid them having to raise employee contributions or reduce pension benefits.

The final option is the least likely of the lot. This is to levy employee National Insurance on pensions in payment (in exchange for removing employee NICs from employee contributions). This idea, proposed by the IFS, is sound in principle. If introduced without any phasing, it could also raise money from rich today’s pensioners who will otherwise end up paying much less in tax on their private pensions than the value of the tax relief they have received. But this move would be a clear breach of Labour’s manifesto. It is hard to see how the Treasury could sell it to the public, especially after the winter fuel allowance debacle.

Why reform pension tax relief?

Some combination of these reforms could raise tens of billions for the Treasury. But this is not just a naked tax grab: there are principled reasons for these measures. I set out the arguments in my recent report Expensive and Unequal: The case for reforming pension tax relief.

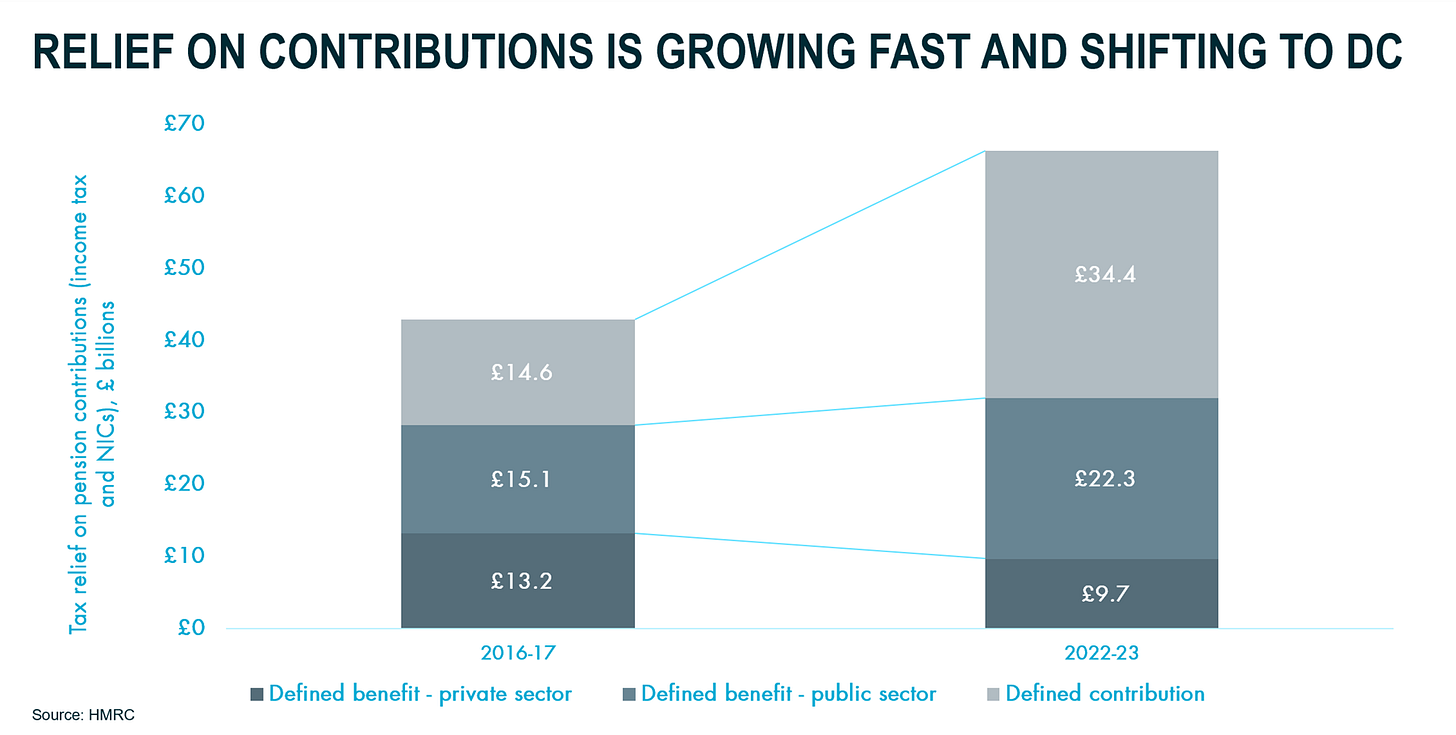

First, pension tax relief is very expensive and getting more so. The amount the exchequer foregoes in tax relief on pension contributions increased by more than 50 per cent in the six years between 2016/17 and 2022/23 (see chart).

All this tax relief is meant to be offset by taxing pensions in payment, but the money raised here amounts to only a little over £20 billion each year (a figure that has been rising much more slowly than the cost of relief). This discrepancy partly arises because a significant proportion of contributions are never taxed, on the way in or the way out. This is very hard to justify given the state of the public finances. The three reforms designed to reduce or curtail the problem are the proposals to: levy NICs on employer contributions; close the loopholes at death; and reduce tax-free lump sums.

Second, pension tax relief is very unequal. Upper and top rate taxpayers make up 19 per cent of employee taxpayers. But they benefit from more than half of pension tax relief (see chart). Partly this is just because they receive so much more in pension contributions. But their share of tax relief is actually disproportionate even to their share of contributions. This for two reasons.

High earners receive a higher share from employer contributions. These are more tax advantaged than employee contributions (which is why so many white collar workers sign-up to salary sacrifice schemes).

Relief on income tax matches the saver’s marginal tax rate. That means basic rate tax payers get 20p in the pound of tax relief, while higher rate payers get 40p in the pound and additional rate payers get 45p. As the chart shows, this leads to a huge discrepancy in income tax relief on employer contributions between basic and higher/top rate payers.

These regressive effects are unfair because richer pensioners do not pay significantly higher tax as a share of their income once they retire. Most pensioners are basic rate taxpayers, even if they were high earners during some of their working life. And those who are not only pay the higher tax rate on the last slice of their income. Either way the average tax rate of former high earners is almost always much lower than the rate of tax relief they received on their pension contributions.

Five principles for reform

At the PLSA conference I argued that reform of pension tax relief was justified as long as it sought to deliver on these five principles:

Tax relief should not HUGELY EXCEED future tax revenues

Tax relief should be BROADLY PROPORTIONATE to people’s earnings and pension contributions

Tax relief should INCENTIVSE AND REWARD steps that create retirement income

Ideally, reform should be FAIR BETWEEN AGE COHORTS

Reform should ‘DO NO HARM’ to high quality DB schemes

These principles will sometimes rub up against each other. The goals of protecting good existing pensions and treating each generation fairly could be used to block reforms that advance the other three principles. But they can also help us think through ‘how’ not ‘whether’ to introduce new measures. Similarly, any moves to reduce today’s very generous tax relief will reduce incentives somewhere in the system. But rewards and incentives can be targeted at those who need the most support, even while saving money overall.

Pulling it all together

Some revenue-generating measures are needed at this Budget. But we also need a long-term journey to a principles-based system of pension taxation, which will take time and thought to deliver. The endpoint after a parliament should be a pension system where:

Employer and employee contributions have the same tax advantages. As things stand high earners get most of their pension from employer contributions, and low earners from employee contributions. Neutrality and fairness point to aligning the national insurance treatment of employer and employee contributions.

Contributions by higher/top rate taxpayers and basic rate payers are treated alike. There should be a single flat-rate of income tax relief. In retirement high earners can expect to pay an average tax rate on their pension that is little more than that faced by middle earners on the basic rate. It is unjust and expensive to give them twice as much income tax relief.

‘Zero taxation’ of pensions is eliminated or severely curtailed. Pension tax relief was created to prevent ‘double taxation’ of the same income. But at the moment the pension system includes too much ‘zero taxation’ where elements of a pension are never taxed.

There is more tax relief for some. The overall cost of pension tax relief should fall. But lots of people who are under-saving should receive more help from government. Basic rate taxpayers should have a default pension deduction of 12 per cent of their total earnings with generous tax relief as part of this. A government match-payment should be created for the self-employed to encourage them to join a new opt-out pension run by HMRC alongside digital tax reporting. And ministers should consider making state pension contributions to people who are away from work for family care.

My last report at the Fabian Society, Expensive and Unequal: The case for reforming pension tax relief, was published in August. I was speaking on its recommendations at the PLSA annual conference on 17 October 2024.