Why child poverty went up and how to bring it down

A post based on my remarks to last week's Prospect Magazine event 'Tackling child poverty: learning from the past, shaping the future'

Britain has two problems of child poverty.

First we have a crisis of ‘deep poverty’. There are one million children living in destitute families, without the money to meet the most basic physical needs.1

Second we have a crisis of ‘broad poverty’, with an extraordinary 4.5 million children (31%) living in families who have a living standard well below that experienced by typical British households.2

‘Deep poverty’ is a result of the state providing insufficient resources to families with children who don’t have another source of income. ‘Broad poverty’ is experienced mainly by families where someone works (72% of poor children have a working parent). It arises when the costs that a family faces exceed their capacity to earn and the government does not make up the shortfall.

The Households Below Average Incomes statistics for 2023/24, published the day after the Spring Statement, paint a picture of this ‘broad poverty’. They show that poor children are overwhelmingly concentrated in households with characteristics associated with high living costs (eg renting, large families) and/or lower earning potential (lone parents, disability, caring for under-5s). Of children below the standard3 poverty line:

34% are in a lone parent family

44% live in a household where someone is disabled4

48% are in a family where the youngest child is aged 0 to 4

49% live in families with three or more children

75% live in a rented home

90% are in homes where the adult(s) are not all full-time employees

We can reduce child poverty either by cutting the share of children in these categories or by reducing the risk of poverty each category faces. The 1997-2010 Labour government had a strong track-record on both these fronts and succeeded in lifting 600,000 children out of poverty (a decline from 33% to 27%). It presided over a fall in the number of children living in families without work, especially among lone parents. And child tax credits boosted family living standards for both working and non-working families, reducing the risk of poverty for all the groups where it was highest.

The Conservative record

The progress made on child poverty under new Labour was more-or-less reversed between 2010/11 and 2023/24. The latest statistics show that child poverty increased by 900,000 under the Conservatives (admittedly in the context of a rising number of children).

This happened at a time when middle incomes after housing costs were barely rising, which means it should have been easier to make progress (the poverty line is linked to median household income). By contrast, from 1997 to 2007 middle incomes were rising very fast so Labour had to redistribute a lot just to stand still.

Another factor should also have made the job of fighting child poverty easier for the Conservatives: parental employment continued to rise. The share of children in households where no one works declined (from 18% to 14%) and the share in which all adults work full time increased (from 22% to 31%).

But three other structural changes worked in the other direction, pushing more children into groups at high risk of poverty.

The share of children living in a household where someone is disabled increased by an extraordinary amount - from 25% to 41% - driven by an increase in both disabled parents and disabled children.

The share of children living in rented housing increased from 39% to 46%.

The share of children in large families increased from 27% to 34%.

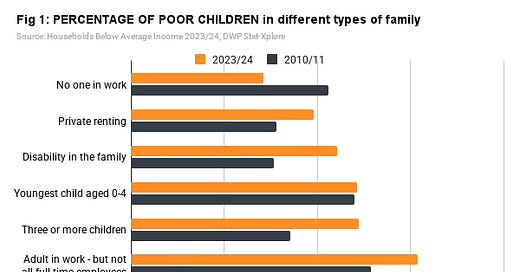

It is important to dwell on these structural changes because they are at least as important in explaining what happened as benefit reforms which normally get most attention. Together these shifts helped change the character of child poverty in Britain as Figure 1 shows. Compared to 2010/11, many fewer poor children now live in non-working families and many more live in a private rented home, in a household where someone is disabled or in a large family.

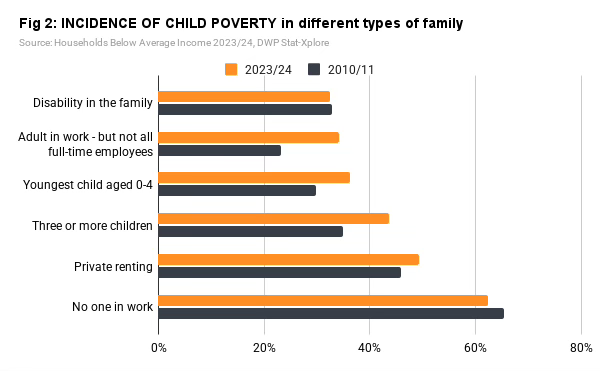

The chances of children in these high-risk groups being in poverty also increased and it is this that can mainly be explained by social security cuts. Figure 2 shows how the incidence of child poverty increased among private renters (up 4 percentage points), families with a child aged 0 to 4 (6 points), families with three or more children (9 points) and working families where the adults are not all full-time employees (11 points).

The increase in poverty in larger families has been widely discussed in the context of the two-child limit on means-tested benefits. But the figures for in-work poverty are perhaps more surprising.

There has been a very large increase in the incidence of poverty in families where the adult(s) are not all full-time employees. Social security top-ups are failing to lift these working families over the poverty line.

Even in homes where all adults are full-time employees 10% of children are in poverty. This is despite the UK’s minimum wage now being among the highest in the world. It is the clearest proof that work alone is not sufficient to escape poverty if families face high costs.

The new government’s child poverty strategy

These new statistics come prior to the government’s child poverty strategy, which is likely to be launched in the summer. In a promising precursor document published last October the government said ‘our focus is on bringing about an enduring reduction in child poverty in this parliament, as part of a 10-year strategy for lasting change’.

Based on the analysis in this post, the strategy can achieve this ambition by looking at four key priorities:

1. Housing

Over the long-term the government should aim to reduce the share of children in private rented housing, the tenure that is most insecure and expensive. That means more social housing and affordable homeownership, as part of the government’s ambition for millions of new homes. In the short-term, legislation now before parliament will increase privately tenants’ rights and protections. Ministers also need to permanently re-link Local Housing Allowance to the cost of rents.

2. Health

The huge rise in children living in families with a disabled parent or child is part of a wider public health emergency. Policy makers are only starting to wake-up to how much the nation’s health has deteriorated - and projections indicate that the position will grow worse.5 In the long-term this can only be tackled by a society-wide public health revolution (which must itself include action to reduce poverty). In the short-term the government’s Get Britain Working agenda needs to prioritise parents with health problems, by supporting and incentivising them to stay in work and find new work. But adequate financial support is also essential for families where a parent has health problem that creates significant barriers to work. The proposed cuts to disability benefits are a backward step.

3. Hours

The strategy needs to help working families to work more hours, with more predictability and control. The government’s employment rights reforms are an excellent start that will make work less precarious for many parents. They need to be followed by robust enforcement (including on the boundary with self-employment) and better parental leave policies. Ministers also need to help families work more by removing barriers and improving financial incentives, especially for second earners and lone parents working part time. The rollout of the new childcare entitlement is a big step forward but incentives in universal credit should also be reviewed, starting with the introduction of a work allowance for second earners.

4. Money

I’ve listed this last but it is the most important. Other action to reduce families’ costs and increase their earnings matter - we need to reverse the structural changes that have bred child poverty. But serious progress requires more generous social security: New Labour’s child tax credits and the Scottish child payment show that spending more directly on children’s allowances makes a difference. As a first step ministers need to act on the two child-limit, the benefit cap and local housing allowance. Then they should raise children’s allowances to accompany the announcement that the adult rate of UC will go up. The Autumn 2025 budget will need to include a significant package of social security improvements if the new strategy is to succeed in cutting child poverty by the next election.

Based on remarks made on behalf of Public First at Prospect Magazine’s event Tackling Child Poverty: Learning from the past, shaping the future on Thursday 3 April.

All the statistics cited in this post are from the latest Households Below Average Income release and are for 2023/24 unless stated.

60% of contemporary median income after housing costs, adjusted for size of household

I’m using the standard measure of poverty which does not take account of the extra costs of being disabled. The incidence of poverty for families where someone is disabled is much higher using the experimental Below Average Resources poverty measure which takes account of the costs of disability.

Health in 2040: Projected patterns of illness in England, Health Foundation, 2023