Measuring what matters

Two newspapers are reporting that the PM is about to announce the five or six key targets that he wants to be judged on at the next election.

In recent days The Times and The FT have reported that Keir Starmer will next month unveil ‘half a dozen “tangible” targets that the government will seek to have delivered on by the time of the next election”, along with ‘a public dashboard enabling voters to monitor his administration’s progress’.

According to the news stories there will be at least five principal goals that ministers will seek to achieve by the time of a 2029 election. These will cover:

Living standards – an increase in disposable household income

Healthcare – 92 per cent of planned treatments within 18 weeks

Childhood – 75 per cent of 5 year olds at a ‘good level of development’

Homes – 1.5 million homes built during the parliament

Energy – on track for net zero power by 2030

There are risks in setting eye-catching targets which are measurable and time-bound, as Rishi Sunak discovered to his cost. Public targets are however a really useful tool for framing the political conversation, creating public accountability and securing eventual electoral recognition. Perhaps even more importantly, they fire the internal processes of government. High-profile targets require ministers to make clear choices, develop evidenced solutions that are sufficient to the task, and maintain focus over time.

In a quiet way Labour has been committed to such targets ever since Starmer announced his five ‘missions’ in spring 2023. The five documents presenting each mission talked mainly about making progress over a decade, but they also set out measures of success to be achieved by the end of one parliament. In opposition Labour went through various iterations of these missions however and never set out a list of its top 5 year goals at pledge-card length. Five months into government, the PM is now ready to say in words and numbers how he wants to be judged.

The five targets

Three of the targets trailed in the press have been mentioned many times by Labour, in opposition and in power. These are the party’s goals on NHS waiting times, housebuilding and green power.

It is nevertheless commendable that Keir Starmer is planning to put them up in lights, since achieving any of them inside one parliament is highly ambitious. Tracking them on a small central dashboard will focus minds across government, as regular updates on the Number 10 website will not necessarily make for good headlines.

The other two putative targets are more of a surprise. The goal of improving early years outcomes was mentioned by Labour in its 2023 Opportunity mission document. But childhood development has not been a focus of campaigning since then. Ministers are making a big statement by saying they want to be judged first on early years outcomes, not educational attainment at later ages. We know early years is a passion for Bridget Phillipson. But to make progress on this goal pre-school education, childcare and early support for parents will need to be a top financial priority for Rachel Reeves too.

Finally, Labour apparently wants to be held to account with respect to family living standards not growth in GDP per capita. The goal of increasing disposable household income was described briefly in the party’s 2023 economy mission document but has been barely mentioned since. This latest pivot is clearly driven by the outcome of the US election and the general consensus that it was inflation that sunk the Democrats.

Until now Labour has talked mainly about its aim of achieving the highest GDP growth in the G7. The focus has been on fixing the drivers of long-term productivity growth to get business firing on all cylinders. This is important and laudable but it will take years to pay off. It is pretty distant from people’s lives and cannot be guaranteed to deliver for family living standards by the next election.

The switch in emphasis towards containing costs and increasing disposable household incomes is therefore welcome. Ten years ago I wrote a report (intended for a future Miliband government!) that called for real median disposable income to be the government’s headline measure of economic success. With co-author Robert Tinker, I argued that this was the best measure of the nation’s shared prosperity:

“Improvements to typical living standards should be the first test of national economic success and this can be best measured by the disposable incomes of mid-income households. GDP is not an adequate measure to capture financial prosperity for typical households, since change in real GDP has been a poor proxy for change to real median household incomes.”

More recently in the Fabian Society’s 2023 pre-election manifesto we again suggested that real household incomes not GDP should be the key yardstick.1 This is not a cosmetic change because the policy solutions for raising GDP per capita and increasing living standards only partially overlap. My former colleagues at the Fabian Society are currently working-up proposals on how to raise living standards for families with incomes at and below the median. Critically, increases in productivity and GDP are not enough. It will also take reforms to labour, housing and consumer markets as well as better social security and public services.

Want more?

As soon as a government asks to be judged on five things, people on the outside will say they got the wrong five. Or ask it to name five more, or 10, or 100. Where is migration or crime or poverty? Even on the issues the government selects, observers will argue that they got the measure wrong.2 But to govern is to choose. And it is really important that Starmer is about to say openly what outcomes matter most to him and what he wants his government to be judged on.

In due course Labour should probably also pick a ‘B list’ and a ‘C list’ of additional goals, as the last Labour government did with its public service agreements. I can imagine ‘mission control’ in the Cabinet Office tracking dozens of indicators of progress and individual departments many more. But the public will never soak up all that detail.

Picking a few big things and sticking with them matters because when everything is a priority, nothing is. This is the start that is needed.

Postscript (for the target junkies!)

As you’ve got this far here are two old lists of proposed targets for a new government.

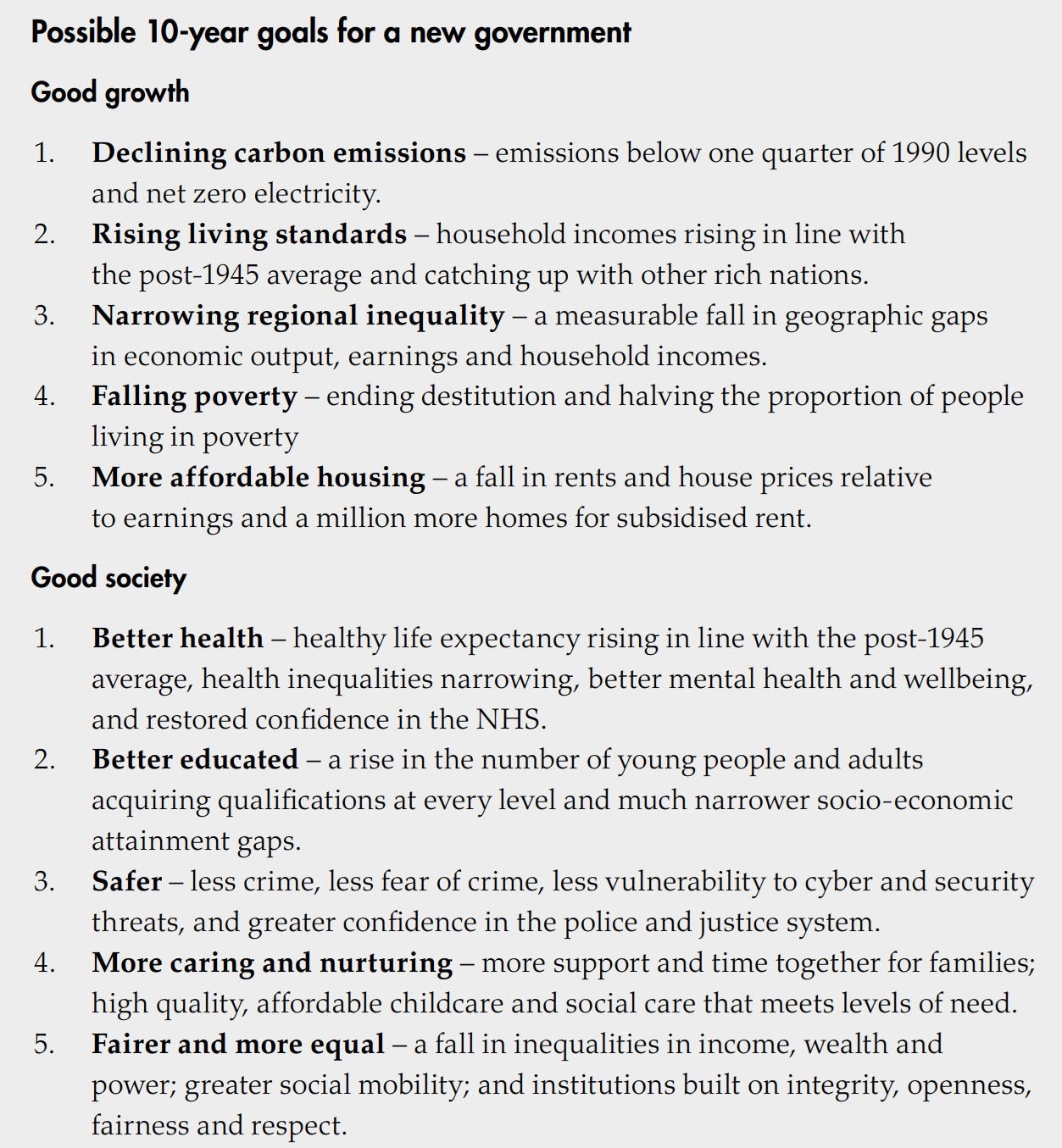

First, a set of ten 10-year goals proposed in the Fabian Society’s 2023 pre-election pamphlet Plans for Power to achieve ‘good growth’ and ‘good society’.

Second, 20 economic indicators for a fair and prosperous society proposed in my 2014 report Measure for Measure.

Note, there is a technical problem with ministers tracking disposable median household income, which by chance I wrote about last week. The best data (from the Family Resources Survey) is always a minimum of one year out of date. If this is the economic indicator the government wants to be judged on at the next election, it will need a workaround to deal with this lag.

For example on health, I know that many policy wonks would prefer an ‘outcome’ measure on healthy life expectancy or health inequalities, not an ‘output’ measure on reducing waiting times. But we are not politicians - and electoral politics demands that ministers focus first on turning around the NHS.